If you work with patients and athletes, you will have noticed that some can tolerate training load better than others. Equally, some athletes tend to “heal quickly”, while others with very similar injuries, spend longer in rehabilitation. In this article, I describe some reasons why some athletes can tolerate rapid changes in load and others can’t!

1. Why Are Some Athletes More Robust and Resilient Than Others?

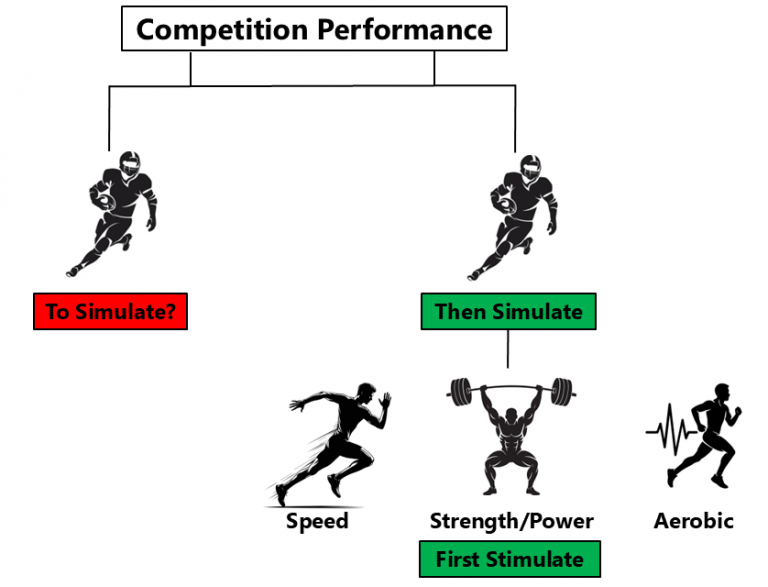

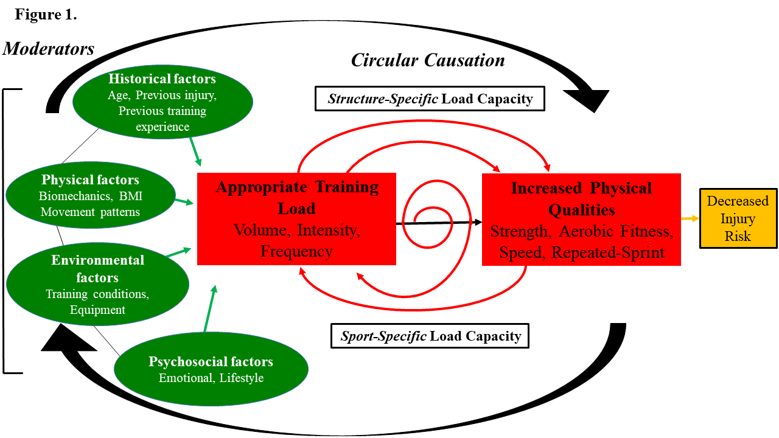

A common question I am asked is “why do spikes in training load result in injury in some athletes and not others – if rapid changes in training load were such a problem, wouldn’t all spikes in load cause injuries?” Apart from the fact that risk does not equal rate, “moderation” can explain this apparent anomaly in the load-injury relationship. A “moderator” acts like a dimmer switch that can either increase or decrease brightness of a light (1). When applied in the context of training load and injury, the presence or absence of a moderator can either increase or decrease injury risk in response to a given training load. For example, athletes with well-developed lower-body strength can tolerate large spikes in training load. However, an athlete with poor lower-body strength who is exposed to the exact same spike in training load, will have a 7-8 times greater risk of injury (2). In this respect, lower-body strength moderates the load-injury relationship. Aerobic fitness, age (chronological, biological and training age), and injury history are also known moderators of the load-injury relationship (3).

2. How Might Moderators Promote Robustness in Athletes?

The ultimate “chicken or egg” question is whether athletes need to first be strong in order to tolerate load, or if loading creates the strength to tolerate further load. My thinking (at least at the moment!) around this topic is that everyone is born with local tissue capacity (some better than others). That local tissue capacity allows people to tolerate an appropriate volume, intensity and frequency of training (NB “appropriate” training load for that individual) (Figure 1). Humans aren’t born with sport-specific capacity, but it develops over time as more training load is applied (4). At present, the “chicken or egg” question remains unanswered, but certainly offers a great challenge for sports medicine and performance professionals to solve!

3. Are All Moderators Related to Physical Qualities?

In terms of the known moderators, most of them have been investigated in team sport athletes. It is highly likely that there are many moderators that have not been uncovered. Equally, it is also likely that they are sport-, position-, and individual-specific – a moderator that is important for a weightlifter will probably differ from a marathon runner. The moderators I have listed above are “physical”, but athletes and patients can experience pain (or maybe fatigue), even in the absence of tissue damage. For simplicity, if we call this load intolerance, the pain is real – it’s just not driven by physical factors. So, if the pain/fatigue is not physical, it must be driven by psychosocial factors. These psychosocial factors will moderate the load-injury, load-pain, and/or load-fatigue relationship and will also determine how fast we can progress training loads.

Final Point

The final point I would like to emphasize is that sports medicine and performance staff make decisions to progress load based on many factors (5) such as:

– Pain response,

– Tissue vulnerability,

– Movement pattern,

– Re-injury risk,

– Psychosocial resilience,

– Temporal stage of tissue healing,

– Inflammatory response to rehabilitation, and

– There are probably others I haven’t even considered!

The best practitioners are the ones who are able to consider the above evidence and reconcile it with their own clinical experience and the athlete/patient in front of them.

Want to level up your programming skills and training principles? Check out our in-person Load Management workshops here!

References

1. Windt J, Zumbo BD, Sporer B, MacDonald K, Gabbett TJ. Why do workload spikes cause injuries, and which athletes are at higher risk? Mediators and moderators in workload-injury investigations. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jul;51(13):993-994. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097255. Epub 2017 Mar 8.

2. Malone S, Hughes B, Doran DA, Collins K, Gabbett TJ. Can the workload-injury relationship be moderated by improved strength, speed and repeated-sprint qualities? J Sci Med Sport. 2019 Jan;22(1):29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.01.010. Epub 2018 Feb 2.

3. Gabbett TJ. Debunking the myths about training load, injury and performance: empirical evidence, hot topics and recommendations for practitioners. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jan;54(1):58-66. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099784. Epub 2018 Oct 26.

4. Gabbett TJ, Nielsen RO, Bertelsen ML, Bittencourt NFN, Fonseca ST, Malone S, Møller M, Oetter E, Verhagen E, Windt J. In pursuit of the ‘Unbreakable’ Athlete: what is the role of moderating factors and circular causation? Br J Sports Med. 2019 Apr;53(7):394-395. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099995. Epub 2018 Nov 13.

5. Gabbett T, Sancho I, Dingenen B, Willy RW. When progressing training loads, what are the considerations for healthy and injured athletes? Br J Sports Med. 2021 Sep;55(17):947-948. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103769. Epub 2021 Apr 9.

Want to read more similar articles? Subscribe to our newsletter below.