How Much is Enough and How Much is Too Much?

In our previous articles we have discussed the importance of (1) building chronic loads and (2) minimizing rapid changes in load in order to build robust athletes. Whether working with elite athletes or “weekend warriors”, the question asked by coaches and sports medicine practitioners is often the same – “How much should I increase training load in order to get the best performance outcome for my athlete, without increasing the risk of injury?” Training load has to exceed capacity in order for an athlete to adapt and eventually improve capacity. However, if training load progressions are too rapid, and the applied load greatly exceeds the tissue’s capacity, then injury results.

But how can practitioners assess whether their athletes are ready to accept the prescribed load? In recent times we have described the acute:chronic workload ratio (ACWR) – an evidence-based approach to safely progress load (1). This method uses the size of the most recent training load (i.e. acute load) relative to the longer-term training load (i.e. chronic load) to build load capacity in athletes. Prior to this method, the “10% rule” was (and in some sports and activities still is) regularly recommended as a useful approach to progress training load. This article will discuss some of the research around training load progressions and provide some practical tips for safely building load capacity.

Does a “10% Rule” Actually Exist?

Anyone who has read a sports medicine or strength and conditioning text has read the passage “Don’t increase training load by more than 10% each week or it will increase the risk of injury!” Limiting training load increases to less than 10% per week is referred to as the “10% rule”. It is extremely popular in endurance sports, particularly running. The implication is that increasing training load by more than 10% per week will increase the risk of injury, while restricting training load increases to less than 10% per week will keep the athlete injury-free. But just how much evidence is available to support the “10% rule”?

Buist et al. (2) studied the influence of ‘normal’ or ‘small’ (i.e. less than 10% per week) increases in training load on injury in novice runners. The group who experienced small increases in training load progressed their training over a 13-week period, while the ‘normal’ training load group reached the same overall training load in a shorter period of time (8 weeks). At the end of the training periods there were no differences in injury prevalence between the slow training progression (21%) and normal training progression (20%) groups. Nielsen et al. (2) also studied training load progression in novice runners. They found that runners who experienced greater than 30% increases in training load per week were more likely to get injured than those who experienced smaller increases in training load. However, they also showed that novice runners could tolerate weekly progressions in training load of ~20-25% – at least for short periods of time.

So what do these results tell us? Firstly, it appears that very large (~30%) increases in training load may increase the risk of injury. Secondly, it is not uncommon for novice runners to increase training load much faster than 10% per week, and at least for short periods of time, tolerate these progressions in training load.

As with any Scientific Principle, Context Matters

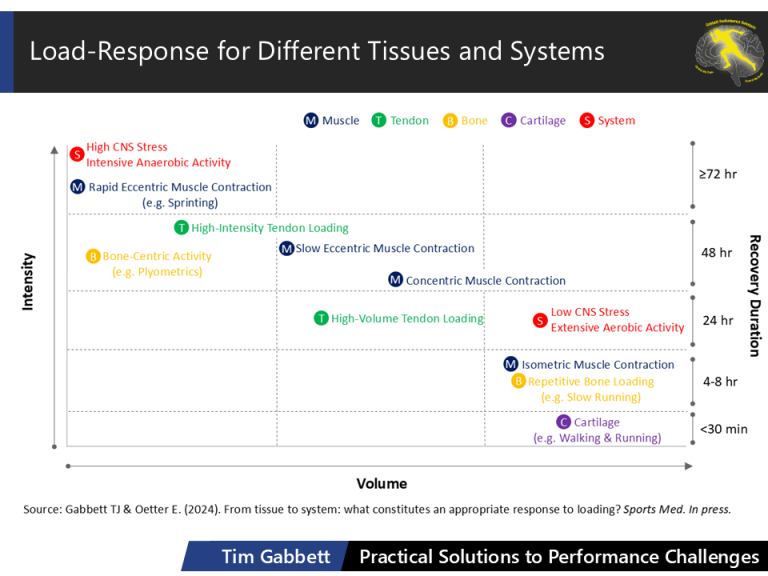

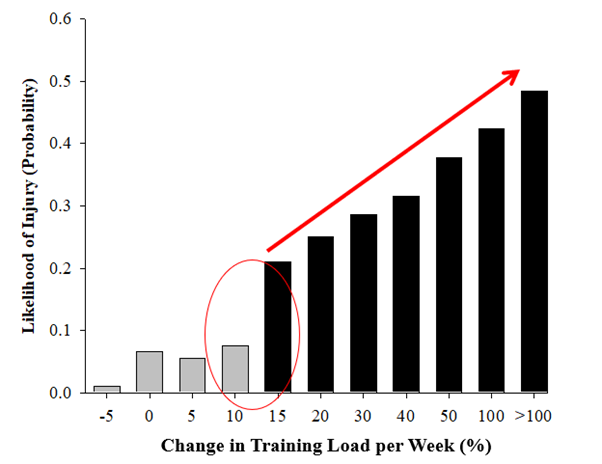

We have previously shown in team sport athletes that when training load increases were limited to less than 10% per week, the likelihood of injury was low (~7.5% injury likelihood) (1). However, the likelihood of injury almost tripled (~21% injury likelihood) when the increase in training load was greater than 15% per week. When weekly training load increases were 50%, the likelihood of injury was as high as 38% (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Likelihood of injury with different changes in training load. Data taken from team sport athletes.

It would be convenient to suggest that to minimize the risk of injury, all athletes should restrict their weekly training load increases to less than 10%. However, with most scientific findings, context matters! Although the general consensus is that rapid changes in training load increases the risk of injury, changes in training load should also be interpreted in relation to the athletes’ chronic load. Athletes with low chronic load have greater scope for increases in training load, while athletes with high chronic load have a much smaller scope to increase their training load. It is much easier to increase weekly training load when the chronic load is near the ‘floor’ than when it is near the ‘ceiling’ (Table 1).

While avoiding rapid changes in training load is generally advisable, coaches and sports medicine practitioners are still encouraged to use common sense when making training progressions. Let’s take the example of an untrained individual (current chronic load is 1 mile per week) who has a goal to run a 10-mile race. If they limited their training load increases to less than 10% per week, by week 2 they would progress to 1.1 miles; week 3 would be 1.21 miles. It would take 26 weeks to build the capacity to tolerate a 10-mile run. In this respect, 10% of “nothing” is still nothing!

Maybe the “10% Guide” is a Better Term!

If the “10% rule” was actually a rule, then weekly increases in training load of less than 10% would consistently result in fewer injuries and increases in training load of greater than 10% would consistently show higher injury rates. Nine percent increases in training load per week would be safe and 11% increases per week would be unsafe! Clearly this is not the case. When progressing training loads, increases of less than 10% should be considered more of a “guide” than a “rule”.

How Do I Know if a 10% Increase is Enough or Too Much?

It is advisable to use more than one piece of information when making data interpretations and training prescriptions. Just as chronic training load should be considered when progressing weekly training loads, the “response” to training should be regularly assessed. For example, if an athlete complains of excessive fatigue, interrupted sleep, mood disturbances, or soreness that presents in the morning and persist at night, then the changes in training load may be more than is tolerable for that athlete. On the other hand, if the athlete is tolerating the applied training load with ease, it may be appropriate to prescribe a greater increase in load. A degree of fatigue is necessary for training adaptations to occur; athletes will not improve if the training stimulus is inadequate. When increasing training load, 10% increases per week can be used as a “guide”, but context (e.g. chronic load, training phase, load tolerance) is still key!

Want to learn more about principles of training, including when to progress your patients training loads? Check out our in-person Load Management workshops here!

References

1. Gabbett TJ. The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:273-280.

2. Buist I, Bredeweg SW, Mechelen van W, et al. No effect of a graded training program on the number of running-related injuries in novice runners: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:33–9. doi:10.1177/0363546507307505

3. Nielsen RO, Cederholm P, Buist I, et al. Can GPS be used to detect deleterious progression in training volume among runners? J Strength Cond Res 2013;27:1471-1478.