In the 1700’s, Benjamin Franklin was famously quoted as saying: “…in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Although social media would have us believe that “age is just a number”, another certainty is that physical qualities decline with age. So, are we destined for a life of aching joints, sore tendons, and an inability to walk up a flight of stairs without gasping for breath? Or are there some evidence-based “cheat codes” that can help us thrive in our later years?

With so much information available on the internet and social media, it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. Should I follow a low-carbohydrate and high-fat diet, plant-based or carnivore diet? Would I benefit from frequent cryotherapy, or would regular sauna exposures be more beneficial? Should I take dietary supplements or even peptides? There may be a role for examining your lifestyle habits, but here are 3 load adaptation strategies that are critical for healthy ageing:

1. Regular doses of low-intensity exercise;

2. Regular strength training;

3. Small doses of high-intensity activity

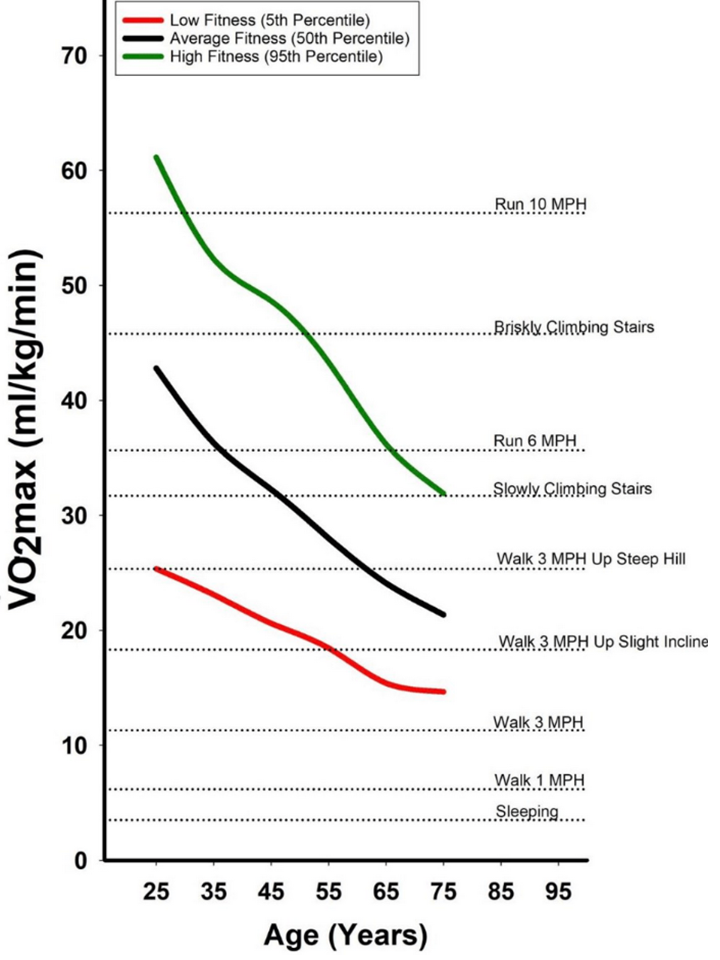

The good news is that it is never too late to begin a structured strength and conditioning program. The world is full of older athletes (including the general population) who are setting PR’s in the gym! But if you are a younger (e.g. < 25 years old) health professional, don’t dismiss the research on ageing. And here’s why – from the age of 25, VO2max decreases by 1% per year (1). After age 40, lean body mass declines by 1-2% per year, with strength decreasing by up to 5% per year (5). An often overlooked fact is that the reductions in aerobic fitness and strength are greater in inactive people, than in recreational and competitive athletes (3). Ultimately, if you have a higher starting point, this translates to a better functional capacity (e.g. lifting ‘heavy’ objects, briskly walking upstairs) as you age.

Check out our Online Certificate Courses here!

So, How Much Strength, Aerobic and Anaerobic Training is Necessary with Advancing Age?

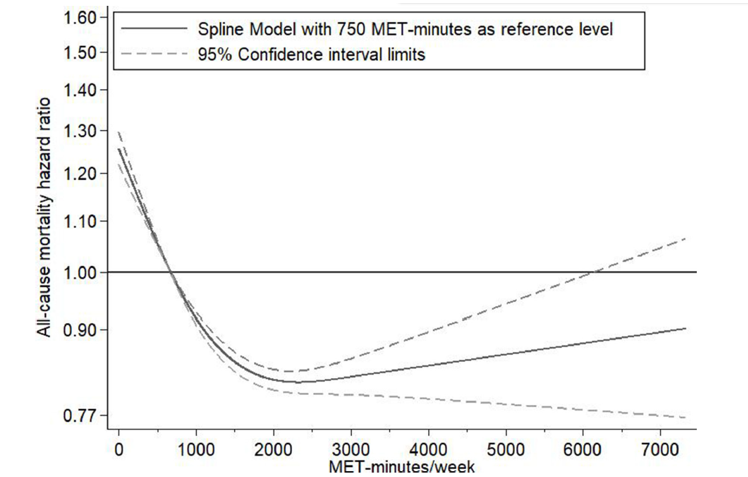

The capacity of the individual will determine how much training is possible, but completing ~150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week (i.e. 5 x 30 minutes) is associated with a low risk of mortality (2). If you walk, run or cycle regularly, try to gradually increase the duration of these activities. To maintain VO2max in general populations, as little as 2, 13 minute sessions per week is needed (7).

Although high-intensity intermittent training has become increasingly popular, a greater frequency of this type of training is not necessarily better for long-term health. In fact, creatine kinase, C-reactive protein, and other inflammatory markers are elevated to a greater extent following high-intensity exercise than similar bouts of moderate-intensity activity. Excessive volumes of high-intensity activity, inadequate recovery, or insufficient lower-intensity exercise may increase the risk of injury or lead to chronic inflammation (4). Keep your high-intensity training sessions short – for health gains, less will be more!

Finally, although an older individual might need a slightly greater frequency of training, as little as 1 session per week is required to maintain strength in general populations. As little as 2 sessions per week and 2-3 sets per exercise is all that is required to maintain strength and lean muscle mass in older adults (6, 7).

Try These “Cheat Codes”!

Next time you’re evaluating the latest fad in training, remember these evidence-based “hacks” – regular aerobic exercise and strength training, and small amounts of high-intensity training. Combined with a regular mobility routine, and you are on your way to living a healthier (and longer) life!

References

1. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Training and Prescription. 10th Edition.

2. Blond K, et al. Association of high amounts of physical activity with mortality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med., 2020;54:1195-1201.

3. Bosquet et al. Effect of training cessation on muscular performance: a meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 2013;23:e140-e149.

4. Cerqueira E, et al. Inflammatory effects of high and moderate intensity exercise – a systematic review. Front Physiol., 2020;10:1550.

5. Keller K, Engelhardt M. Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Musc Lig Tend J., 2014;3:346-350.

6. Peterson MD, et al. Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev., 2010;9:226-237.

7. Spiering BA, et al. Maintaining physical performance: the minimal dose of exercise needed to preserve endurance and strength over time. J Strength Cond Res, 2021;35:1449-1458.

Level up your sport performance skills with Tim’s online certificate courses!