In our recent article, we addressed best practice in high-performance organizations, and how the application of existing research alone does not constitute evidence-based practice. A major challenge with relying on published research to inform practice is that the research process takes time – it can take years for research to go from the “laboratory to the field”. Recently, it was estimated that an average of 17 years was needed for research to be translated into practice.1 By the time the evidence reaches the coalface of professional sport, the problem no longer exists, or the staff charged with solving the problem have retired! But the arms race is on – and a unique opportunity exists for high performance organizations willing to embrace the power of applied research.

Service Delivery Without Conceptual Involvement is Not Effective Sport Science

Historically, sport science and medicine providers have been viewed as the “service providers” to high-performance coaches and athletes. They provide the testing, the programs and the treatment to ensure athletes are physically and mentally prepared for the demands of competition. Although the role of these practitioners has evolved over the years, sports medicine and performance staff are still viewed as critical “cogs” in the high-performance machine. Importantly, these practitioners do not simply provide a service with limited conceptual involvement – the support they offer to athletes is designed to answer specific questions (e.g. “If we trained this way would we get stronger?” “If we treated an injury with a new technique, could we have a faster return to sport?”). In this respect, research forms part of the service delivery model provided to athletes. It may not be performed with the intent of publication, but any service delivery that begins with a question, and the practitioner seeks to find an answer to that question, is a form of research.

Practice-Based Evidence – The New Frontier

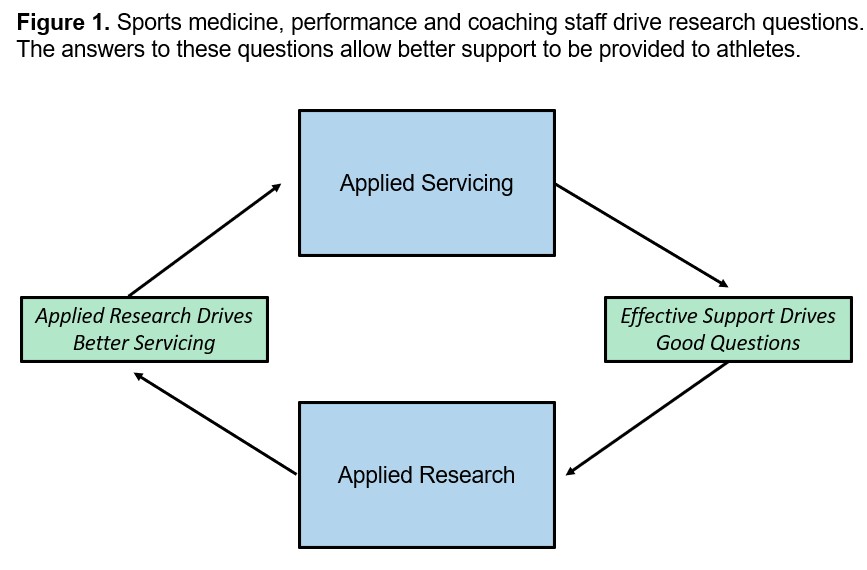

Given the protracted length of time between the publication of new findings and application in the field, astute high-performance organizations are proactively developing applied research departments to ensure their athletes and coaches have access to the very latest sport-specific research. The applied researchers work collaboratively with field-based sports medicine and performance staff to answer questions that are directly relevant to the organization. Importantly, this approach allows the organization to have ‘real-time’ access to cutting-edge research that can have immediate benefits to the organization (Figure 1). The length of time to translate research to practice is significantly reduced! A higher quality of support is provided to athletes, which in turn drives further questions – the answer to these questions allows even better support to be provided to athletes!2 A major advantage of this model over traditional university-based research is that high-performance athletes are studied in their normal operational environment, limiting the translational difficulties associated with contrived experimental protocols conducted on non-elite populations (e.g. university students).

So, What’s Holding Teams Back?

The vast majority of funding in academic institutions is devoted to basic research –research that results in general knowledge that may form the basis to answer important practical problems but is performed without any thought of practical outcomes.1 Far less funding is provided to clinical research (e.g. research that involves interventions or the development of new technologies). This has resulted in 2 significant problems:

- Little incentive is provided to academic researchers to perform applied research, and

- The research that is being performed is viewed by practitioners as being too far removed from the “real world” challenges faced in sport.

In many cases, practitioners view research as a process that involves test tubes and lab coats but has minimal impact on their day-to-day operations! But it doesn’t have to be this way! Research does not have to be theoretical – it can have strong practical applications that are immediately accessible to coaches and sports medicine practitioners to improve athlete performance.

An Example of How Research Can Be Immediately Translated to Practice

There is a place for basic research, but not all research requires complicated or contrived experimental protocols. This is particularly important in the fast-paced world of high-performance sport. Applied sport scientists can also use service delivery or repeated, careful observations in training and/or competition environments to answer performance questions. Here’s an example of how it works in practice:

Is Agility Affected More by Change of Direction Speed or Decision-Making Factors?

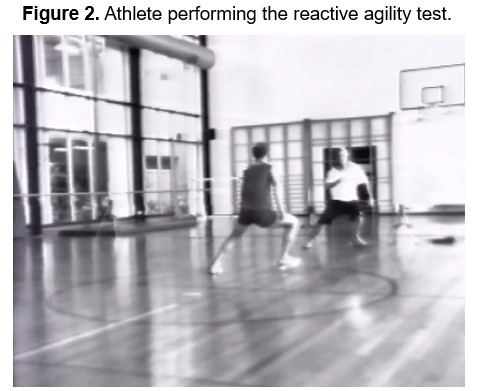

In this project, we had team sport players perform a reactive agility test, where they had to “read and react” to game-specific cues presented by a tester3 (Figure 2). During the test we measured decision time (i.e. how long did it take for the player to process the cues presented by the tester and initiate a response?), decision accuracy (i.e. did they make the correct decision?), and movement time (i.e. how fast did they change direction after making their decision?). Effectively the test allowed us to identify the players who were “fast movers” and those who were “fast thinkers”! The results allowed performance staff to identify the relative agility strengths of their players – which players were limited by change of direction speed and which players were limited by decision-making factors. Individual-specific training interventions were then applied to enhance agility qualities (Figure 3).

Making it Work in Practice!

Applied research, when performed collaboratively between researchers and team staff, can offer a competitive advantage to high-performance organizations. In the future, I predict that all elite organizations will establish centres of applied research (or research and development arms) to support the day-to-day practices of sports medicine and performance staff.4 After building a career that has encompassed both applied servicing and research, here’s some tips to ensure you develop effective translational research strategies for your high-performance organization:

- Good research starts with a good question!

Take the time to understand the question you want answered. If you have a refined question, there will be greater clarity on what research design is needed to answer that question.

- Take the time to learn the sport!

Some of the best sport science I have been involved in is where I have done nothing at all! Spend time with coaches in their environment – on pool deck, the field and court. This is their “lab”, and every day they are testing hypotheses! (i.e. “Did my session achieve its objective today?” “When I changed the numbers in this drill, what was the outcome?”). The more you immerse yourself in the sport, the more time you spend with athletes and coaches, the better your understanding of the real problems that exist for that sport.

- Avoid collecting numbers looking for a question!

While some of the best scientific findings have been made by accident (e.g. Watson and Crick’s discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA), most research projects start with an end-point in mind. Having a clear picture of the problem will provide clarity on what data needs to be collected.

- Not all research requires complicated experimental designs!

Sport is complex, but it doesn’t need to be complicated! The best research often stems from simple performance questions. Your research will never answer every single performance question, but the benefit of simple questions is that you’re far more likely to provide a practical solution for coaches.

- Don’t let the tail wag the dog!

Not all people within your organization will have research experience or skills – that’s OK, we don’t want our high-performance organizations to become a laboratory. In these cases, you may have to seek assistance from independent researchers and experts. But remember, as organizational leaders (e.g. general managers, high-performance directors, directors of sports medicine), no-one will understand the specific performance issues effecting your organization better than you! So, it is best if you drive the research question. Independent researchers may provide expert advice on the best research design or analysis to answer your specific question, but don’t let the tail wag the dog!

- Focus on performance outcomes!

All research is interesting, but not all of it is important! When deciding on which research questions to pursue, ask the question “will this research make my athlete/s better (i.e. faster, stronger, fitter, more skilful)?” If the answer is “yes”, then the project might be worth pursuing.

Creating an Uneven Playing Field!

Often, little separates performances of the most elite teams. The quality of the support provided by sports medicine and performance staff, and the way these departments collaborate with each other, can contribute to on-field success. The development of applied research “arms” has the potential to contribute further to these successes by providing high-performance organizations with a competitive advantage over their opposition and immediate benefits for their athletes.

Want to gain an edge over your opposition? Contact us to hear how Tim can help your organization!

References

1. Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med 2011;104:510-520.

2. Gabbett TJ, Kearney S, Bisson LJ, Collins J, Sikka R, Winder N, Sedgwick C, Hollis E, Bettle JM. Seven tips for developing and maintaining a high performance sports medicine team. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:626-627.

3. Gabbett TJ, Kelly JN, Sheppard JM. Speed, change of direction speed, and reactive agility of rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res 2008;22:174-181.

4. Suchomel T, Comfort P, Gabbett T, Jones M, Nimphius S, Stone M. Current issues and future research directions in sport science: a roundtable discussion. Strength Cond J 2023; in press.